The countryside has always been the economic and social heart of rural areas, but it also hides a less visible reality: an atmosphere that changes in rhythm with tractors, barns, and fertilisers. For years, agriculture and livestock farming have quietly sustained entire communities, while their emissions —those “invisible chimneys” of the primary sector— have shaped the climate without much public attention. Today, emission inventories leave no doubt: methane released by ruminants, nitrogen oxides from agricultural soils, and ammonia from intensive livestock farming are key pieces in the climate puzzle and in the air qualityAir quality refers to the state of the air we breathe and its composition in terms of pollutants present in the atmosphere. It is considered good when poll...

Read more breathed by millions of people in rural and peri-urban areas.

To these gases we must add CO2 and volatile organic compounds, which feed the formation of tropospheric ozone and secondary aerosols, with direct effects on human health. In other words: what happens in the countryside doesn’t stay in the countryside.

At the same time, social and regulatory pressure is increasing for food production to become traceable, measurable, and scientifically justified in terms of emissions across all its processes —from the enteric fermentation of ruminant digestion to manure management.

As researcher Nancy Harlet Esquivel Marín recently pointed out, a single cow can emit between 250 and 500 litres of methane per day —a figure that illustrates the scale of the challenge when multiplied by the millions of cattle worldwide.

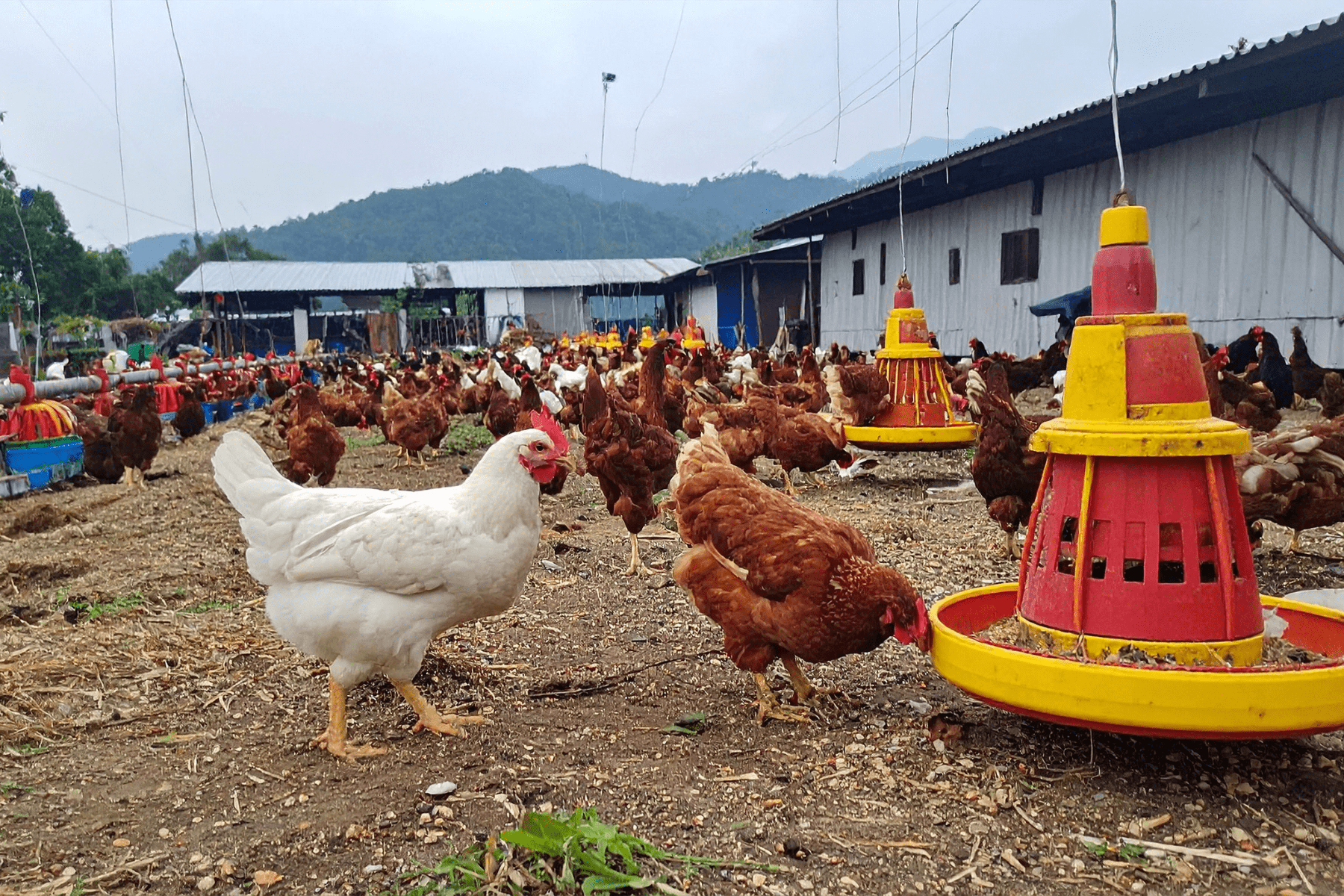

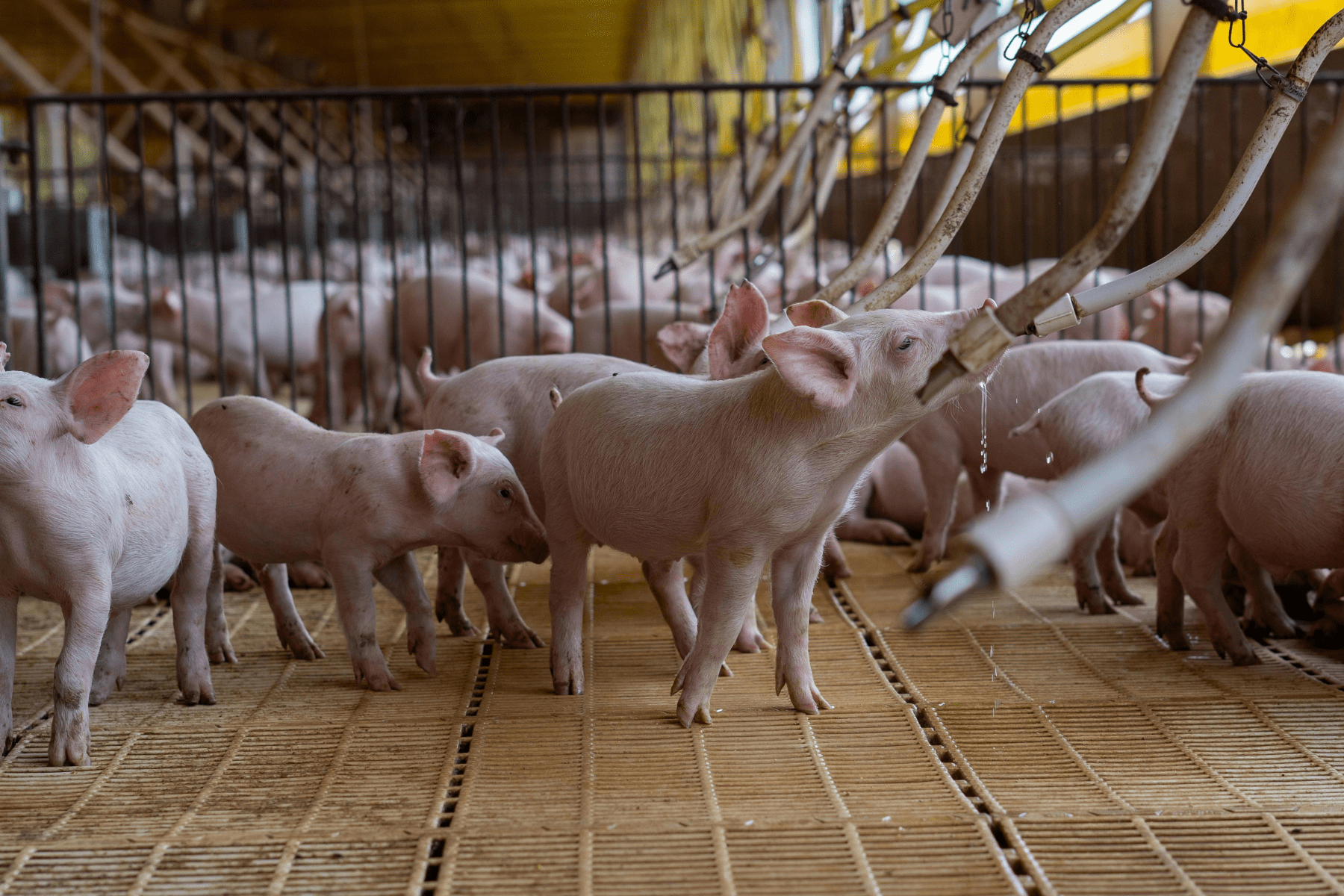

The EU is using its LIFE and Horizon programmes to demonstrate that reducing ammonia emissions from livestock farming is technically feasible along the entire manure management chain, with projects achieving reductions of 60–90%, and even up to 95% in pig farms equipped with advanced monitoring and reduction systems. At the same time, the Commission stresses that the challenge has shifted from technical feasibility to financing, scalability, and the removal of economic and regulatory barriers preventing widespread adoption by the sector.

This article explores the crucial —and often uncomfortable— intersection between food production, the atmosphere, and public well-being, to understand how an essential sector can transform itself by choosing to measure, manage, and reduce its emissions.

Air Quality Innovation in Just 1 Click

Stay informed about the air you breathe!

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive the latest updates on environmental monitoring technology, air quality studies, and more.

Sources of emissions in livestock and agriculture

From animal metabolism to manure storage and the application of fertilisers, every link in the agricultural production chain emits compounds into the air that can now be measured accurately and managed efficiently, with a focus on public health protection.

Below, we examine the main sources of emissions in this primary sector to understand why livestock and agriculture are no longer merely productive or economic activities, but central contributors to global atmospheric change.

Today, agricultural and livestock emissions can be accurately measured and managed efficiently with a view to protecting public health.

Natural emissions from animal metabolism

Domestic livestock, being ruminants, undergo enteric fermentation during digestion, transforming plant fibre into energy. However, this process also releases methane as a by-product, which the animal expels mainly through belching. More than 90% of livestock methane emissions from ruminants are generated in this digestive process, making cattle and sheep the main biogenic sources, unlike pigs, whose impact on climate change is mostly linked to manure management.

In the European Union, methane from enteric fermentation represents 49% of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), while N2O from soils accounts for 30% and methane from manure management 17%. Likewise, ammonia emissions —90% of which come from agriculture— significantly contribute to air and water pollution across Europe.

Food production is directly linked to climate mitigation and public health risks.

Manure management and slurry storage

When animal waste is stored as solid manure or slurry, the organic matter and nitrogen compounds degrade, emitting ammonia, methane, and carbon dioxide. Under conditions of high temperature, poor ventilation, and large exposed surfaces —favouring both anaerobic fermentation and ammonia volatilisation— emission peaks rise sharply in facilities such as barns, lagoons, and pits. Implementing measures such as covering storage areas, separating degradation phases, acidifying slurry, or diverting it to anaerobic digestion systems can significantly reduce emissions throughout the entire manure management process.

Use of fertilisers and agricultural tillage

In agriculture, the application of nitrogen fertilisers —both mineral and organic— generates emissions of ammonia (NH3)Invisible yet powerful: ammonia (NH3) is a colourless gas which, although naturally present in the atmosphere in small amounts, can become an unwelcome ene...

Read more and nitrogen oxides (NO, NO2, and N2O) that reach the soil and atmosphere, particularly when fertilisers are applied on the surface under dry and windy conditions. Tillage operations, heavy machinery traffic, and the handling of dry soils lift agricultural dust and coarse particles (PM10), which can travel tens of kilometres and contribute to regional increases in particulate matter levels. In ammonia-rich atmospheres, these emissions interact with other atmospheric precursors to form secondary aerosols and enhance tropospheric ozone formation, increasing the risks faced by public health and ecosystems.

Agricultural activity accounted for 87% of total ammonia emissions in the United Kingdom in 2023, mainly from livestock manure and nitrogen fertilisers. Pommier, M. et al. (2025).

Agriculture and food systems have a profound impact on the atmosphere,

Impacts of livestock emissions on air quality and climate

Livestock emissions are no longer an issue confined to farms — they have become a key factor influencing air quality and climate, with measurable effects on human health and the balance of the carbon and nitrogen cycles. What happens in a barn, a slurry lagoon, or a fertilised crop field often ends up as ammonia, fine particles, or methane in the atmosphere, directly linking food production to climate mitigation and public health risks.

Local pollution and health effects

At a local level, in areas where intensive livestock farming is practised, high concentrations of ammonia and fine particles (PM2.5) are recorded — both from direct emissions and from secondary aerosol formation derived from ammonia.

Proximity to intensive farms is associated with eye and respiratory irritation, exacerbation of childhood asthma, and a higher risk of respiratory problems among workers and nearby rural residents. These local emission sources can also contribute to regional pollution episodes: livestock ammonia reacts with nitrogen and sulphur oxides to form a significant fraction of anthropogenic PM2.5 in industrialised regions.

2. - Kunak" width="1800" height="1200" /> Methane emitted from enteric fermentation and manure management has a global warming potential far greater than that of CO2.

Climatic effects of methane and associated gases

Methane emitted from enteric fermentation and manure management has a global warming potential far greater than CO2: over a 100-year period, each tonne of CH4 warm the atmosphere around 27–30 times more than a tonne of CO2, and over 20 years that ratio exceeds 80 times.

Agriculture —and particularly the combined CH4 and N2O sources within the AFOLU (Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use) sector defined by the IPCC— contributes several gigatonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions annually, placing farming at the centre of the global carbon and nitrogen cycle debate.

Nitrogen management on croplands is one of the key challenges of the 21st century, as we must balance food production with pollution mitigation. Tai, A.P.K., Luo, L. & Luo, B. (2025).

Against this backdrop, national emission inventories have become a strategic tool: they allow quantifiable and comparable metrics of livestock contributions to climate and air pollution, and form the basis for designing reduction policies and implementing reliable monitoring systems.

Emissions from livestock farming and agriculture also alter the climate and worsen air quality.

Environmental monitoring: how to measure and manage agricultural emissions

The environmental monitoring of agricultural emissions has evolved from academic analysis into an indispensable operational tool for compliance with regulations such as the Industrial Emissions Directive and the objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) post-2027.

Remote sensors, fixed monitoring networks, and platforms such as the European Innovation Centre for Industrial Transformation and Emissions (INCITE) make it possible not only to quantify in real time methane, ammonia, and other air pollutantsAir pollution caused by atmospheric contaminants is one of the most critical and complex environmental problems we face today, both because of its global r...

Read more, but also to optimise mitigation strategies on farms through high-resolution, traceable spatial and temporal data. This approach turns accurate measurement into a competitive advantage for the agricultural sector.

Which gases should be measured and why

Methane is the main by-product of enteric fermentation in ruminant digestion and also arises from anaerobic digestion in slurry pits. Its high global warming potential (GWP) and its contribution to 30–40% of agricultural GHG emissions in Europe justify continuous monitoring.

In agricultural contexts, a high GWP means that 1 kg of CH4 traps 27–30 times more heat than 1 kg of CO2 over 100 years, or up to 84 times over 20 years, explaining why it is prioritised in continuous monitoring despite its short atmospheric lifespan (around 12 years).

Ammonia (NH3), volatilised from fresh slurry and nitrogen fertilisers, is a priority gas for monitoring due to its role as a precursor of secondary PM2.5 and its contribution to ecosystem eutrophication. Livestock farming accounts for up to 90% of total ammonia emissions in countries with intensive production.

CO2 and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are released from soils through root respiration and the degradation of crop organic matter. Their presence is exacerbated by tillage, soil compaction, and the passage of heavy agricultural machinery under dry conditions.

The toxic and odorous gas H2S (hydrogen sulphide) is naturally produced during the anaerobic digestion of sulphur-rich organic matter such as livestock manure or agro-industrial waste processed in biodigesters to generate biogas. Due to its strong odour, it also affects the social acceptance of livestock operations.

Measuring these gases and compounds accurately enables regulatory compliance, the detection of leaks, and the optimisation of nutrient cycles in production facilities.

The debate over whether livestock is the largest contributor to GHG emissions has intensified since the FAO’s 2006 report “Livestock’s Long Shadow”. The issue has continued to grow, highlighting the tension between the industry’s importance for food security and livelihoods; therefore, monitoring GHG emissions from this sector is vital. Nugrahaeningtyas, E., Lee, J. S., & Park, K. H. (2024).

Sensor technology and environmental monitoring stations

Continuous monitoring of agricultural emissions has proven essential for obtaining real-time data that ensure regulatory compliance and enable on-site operational optimisation. On farms, daily temperature and wind variations can greatly increase pollutant leaks into the air.

Compared to manual methods, which can show 10–26% calibration errors and days-long delays, continuous monitoring uses electrochemical and optical sensors that provide hourly traceability, automatic validation, and meteorological correlation, aligning with directives such as the IED and MCERTS standards.

Continuous monitoring provides complete time series data, enables the early detection of emission peaks, and reduces long-term operational costs by achieving valid data rates above 95%, even in complex rural environments.

Electrochemical sensors used in monitoring stations for gases such as NH3 and H2S detect redox reactions (reduction-oxidation) with precision at parts per billion (ppb) levels, while optical sensors such as laser/NDIR instruments for CH4 and VOCs measure non-contact spectral absorption, compensating for humidity and temperature interferences using proprietary algorithms.

Kunak AIR Pro stations can integrate up to five interchangeable gas sensors (CH4, NH3, H2S, VOCs) alongside MCERTS-certified PM1/PM2.5/PM10 particle sensors. They also incorporate meteorological parameters and can operate autonomously using solar power, allowing deployment in remote locations such as slurry lagoons or barns.

Cloud data and smart analytics

The Kunak AIR Cloud platform transforms collected data into heat maps, pollution roses (polar charts showing contaminant direction, frequency, wind speed, and concentration), and automated geolocated alerts. This enables the identification of NH3 emission points near lagoons or CH4 concentration trends linked to livestock feeding cycles.

By correlating emissions with meteorological variables such as wind, temperature, and relative humidity, algorithms can predict pollution peaks and optimise ventilation or cover systems in real time.

Automatic reports generated daily or weekly by the Kunak Cloud platform provide ESG traceability to verify the sustainability of facilities for certifications, owners, and investors.

Moreover, this facilitates compliance with the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which requires NH3 reduction, and the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED), mandatory for farms with over 40,000 poultry or more than 2,000 pig places.

APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) are sets of protocols that allow different software systems to communicate and share data automatically and in a standardised way. Data are transferred directly to enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems such as SAP or SCADA (industrial process control to automatically activate ventilation when peaks are detected). These functions enable the real calculation of carbon footprintIn a world increasingly affected by climate change, understanding how our everyday actions contribute to its worsening has become essential. The carbon foo...

Read more per animal or batch, generate ESG reports to justify CAP funding, export data to national inventories such as Spain’s SEI, report GHG emissions officially, and optimise the purchase of low-emission inputs.

Keeping cows grazing outdoors for 200-300 days a year reduces methane by 25% per kilogram eaten and improves milk with more protein.

Mitigation strategies and best practices in the agricultural and livestock sector

Mitigating emissions in the agricultural and livestock sector has evolved from voluntary initiatives to mandatory strategies for accessing CAP funding and complying with the revised IED, where reductions in NH3 and CH4 are measured in specific, verifiable percentages. From feed additives to biodigesters and IoT sensors, farms that adopt these technologies not only minimise their atmospheric footprint but also generate additional income through biogas production and ESG certifications.

Below, we analyse several interventions capable of transforming waste into agricultural resources while optimising productivity through the precise air quality data collected within farm facilities.

Mitigating emissions in the agricultural and livestock sector has evolved from voluntary practices to the current mandatory strategies.

Optimising livestock feeding and digestion

The inclusion of natural additives such as Asparagopsis seaweed (bromoform), essential oils, and tannins in livestock diets helps modulate ruminal microbiota, inhibiting methanogens and reducing enteric CH4 emissions by up to 30% without compromising feed quality or milk production.

The feed additive 3-NOP or 3-nitrooxypropanol (Bovaer®), approved by the EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) in 2022 as the first selective enteric methane inhibitor for ruminants, works by blocking one of the enzymes used by methanogenic archaea —strictly anaerobic microorganisms that produce methane as a metabolic by-product in oxygen-free environments such as the rumen. Its action reduces CH4 emissions by 20–30% in dairy cows and up to 45% in beef cattle, without affecting productivity or leaving residues in milk or meat, as it degrades naturally within 3–4 hours.

Genetic selection also identifies ruminant lines with lower methanogenic activity, such as Friesian or Holstein cows that produce 15–20% less CH4 per kilogram of milk thanks to genomic markers promoting more efficient rumens. Breeding elite bulls with animals showing cleaner digestion results in offspring with a 10–12% decrease in emissions without sacrificing performance.

Keeping cows grazing outdoors for 200–300 days a year replaces up to half of their feed with fresh grass. This reduces methane emissions by 25% per kilogram of feed consumed and improves milk protein content (+0.2–0.3%). Rotational grazing enhances soil cover and promotes animal welfare while saving 15–20% on feed supplements. Combined, these actions lower pollutant emissions, increase profitability, and recover investment within 2–3 production cycles.

Advanced manure and slurry management

Installing floating covers over slurry lagoons prevents oxygen ingress and captures NH3 and CH4, achieving emission reductions of 60–80% depending on whether rigid or flexible geomembranes are used. Meanwhile, biofilters and phase separators stabilise manure before it is applied as fertiliser.

Anaerobic digestion in biodigesters transforms slurry into biogas, making up to 60% of CH4 recoverable. Whether used to generate electricity or to fuel heating systems for self-consumption, the process also produces digestate —the nutrient-rich residue (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) left after anaerobic digestion— which is employed as a stable organic fertiliser with low volatile nitrogen (less odour and pathogens than raw slurry) and soil-improving properties. This is an effective way to close the nutrient cycle while complying with IED limits for intensive livestock operations.

Precision agriculture and environmental control

In agriculture, the use of IoT sensors enables monitoring of soil moisture, pH, and evapotranspiration to implement variable-rate irrigation systems that minimise nitrate leaching and VOC release. These sensors can also regulate ventilation activation in livestock facilities to dilute NH3 depending on wind and temperature conditions.

There are also integrated platforms that combine air monitoring data with soil (moisture and nitrogen) and water (nutrients) parameters, predicting emissions and optimising fertiliser use with doses adapted to the specific surface area. In smart farms, this convergence reduces input use by 20–30% and anticipates pollution peaks through predictive alerts.

Regulations and international commitments on agricultural emissions

Regulatory pressure on agricultural emissions has intensified, resulting in binding commitments that make reducing NH3 and CH4 an essential condition for accessing subsidies and participating in international trade. From national directives to global strategies, the agricultural and livestock sector now operates under clear deadlines and measurable targets that drive the transition towards circular models.

The EU NEC Directive (2016/2284) sets strict national limits for NH3 (11–19% reduction vs 2005) and agricultural methane, requiring each Member State to develop national action plans, supported by annual emission inventories and penalties for non-compliance. The IED regulation (Directive 2010/75/EU, updated in 2024) obliges large intensive farms (those with more than 40,000 poultry or 2,000 pigs) to obtain an integrated environmental permit from regional authorities, just like industrial plants.

To be approved, farms must apply BAT (Best Available Techniques) —such as slurry covers, biofilters, or acidification systems— that can reduce NH3 emissions by up to 70%, as well as ensure continuous sensor-based monitoring (not annual sampling) validated to report emissions online. Non-compliance can result in fines or closure, while approval grants access to CAP subsidies and reduces operational costs in the medium term.

The “Farm to Fork” strategy encourages agricultural and livestock operations to use 20% less nitrogen fertiliser and 50% fewer pesticides by 2030. This approach integrates livestock farming into the Green Deal through CAP-aligned schemes that reward the adoption of biodigesters and low-CH4 diets. In parallel, voluntary carbon credit programmes such as Verra or Gold Standard enable farms to certify measurable reductions, monetising digestate or extensive grazing practices within emerging markets.

Agricultural and livestock farming should be an industrial activity that promotes clean local air.

European regulatory framework for livestock emissions

This table summarises the main emission limits, reference values and reduction targets applicable to livestock farming in the European Union. It brings together the criteria established by the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED), the NEC Directive and the IPCC methodologies, with particular focus on key pollutants such as ammonia (NH3) and methane (CH4)Methane, known chemically as CH4, is a gas that is harmful to the atmosphere and to living beings because it has a high heat-trapping capacity. For this ...

Read more. Its aim is to provide a clear overview of when regulatory requirements apply, what emission levels are considered benchmarks, and what reductions can be achieved through the application of best available techniques (BAT).

Emission limits and reference values for livestock farming in the EU

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollutant | Source / Regulation | Threshold / Limit | Reference value | Reduction target |

| NH3 | IED BAT (pig farming) | > 2,000 places | 2.2 kg NH3 / animal place / year | Up to 70% with BAT |

| NH3 | IED BAT (poultry farming) | > 40,000 birds | 0.13–0.3 kg NH3 / animal place / year | Up to 60% with BAT |

| NH3 | NEC Directive Spain 2030 | National | Reduction target of 16% vs 2005 (−400 kt) | −16% |

| CH4 | Enteric fermentation (livestock) | IPCC Tier II | 100–200 kg CH4 / head / year (dairy) | 20–30% with additives |

| NH3 | IED threshold for installations | Large intensive farms | Environmental permit required | Application of BAT |

Benefits of environmental monitoring for the agricultural sector

Environmental monitoring in the agricultural and livestock sector helps reduce losses by detecting early NH3 and CH4 peaks. A 10% reduction in volatilisation can translate into €50–100 saved in fertilisers per hectare, while also reducing infrastructure corrosion and optimising ventilation to cut energy consumption by 15–20%.

Accurate, traceable data allow farms to plan feeding cycles (lower enteric CH4 emissions), regulate variable irrigation, and treat slurry according to wind direction and humidity. The result is more milk per hectare with 20% fewer inputs, aligning production with climate action goals.

Agriculture and food systems have a profound impact on the atmosphere, primarily through substantial emissions of reactive nitrogen compounds from croplands and livestock systems, but also through other air pollutants such as primary particles (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), SO2, and VOCs, resulting from agricultural burning, energy use across food systems, and deforestation for agricultural expansion. Tai, A.P.K., Luo, L. & Luo, B. (2025).

Platforms like Kunak AIR Cloud help secure certifications (ISO 14001, carbon footprint) and voluntary credits (Verra), monetising operations through reductions of up to €50/t CO2eq. They also support access to CAP subsidies covering 30–40% of investments in sensors and environmental monitoring stations.

Equally important are the improvements in community relations —with neighbours and authorities— through predictive alerts that prevent odour complaints, provide transparent public air quality maps, and build trust by positioning the agricultural facility as an ally of local clean air.

In areas where intensive livestock farming is practised, high concentrations of ammonia and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) are recorded.

FAQs: livestock, emissions and air quality

What pollutants does livestock farming produce?

Livestock farming primarily emits methane (CH4), a potent greenhouse gas released during ruminant digestion. It also produces ammonia (NH3), which causes unpleasant odours and contributes to fine particle formation in the atmosphere, along with various nitrogen oxides (NOx) from manure and fertiliser management.

Additionally, livestock activity generates particulate matter (PM)Atmospheric particulate matter are microscopic elements suspended in the air, consisting of solid and liquid substances. They have a wide range of sizes an...

Read more and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that degrade air quality. Combined, these emissions affect both climate change and local air pollution.

How do livestock emissions affect human health?

Livestock emissions promote the formation of fine particles and tropospheric ozone, two pollutants capable of penetrating deeply into the respiratory system. Prolonged exposure is associated with lung irritation, increased asthma symptoms, and higher risks of respiratory infections.

These pollutants also impact cardiovascular health, as fine particles can enter the bloodstream and contribute to hypertension and heart disease. Overall, pollution from livestock operations poses an additional public health risk.

What solutions exist to reduce agricultural emissions?

Reducing agricultural emissions involves optimising manure management to minimise gas release and improve storage and treatment. It is also essential to enhance ventilation systems in livestock buildings to disperse contaminants and lower their concentration in the air.

Moreover, adjusting animal diets can decrease methane production, while sensor technology enables the detection of leaks or high pollutant levels in real time, allowing rapid mitigation. Together, these measures make agriculture more sustainable and less harmful to the environment.

Why is it important to monitor agricultural gases?

Monitoring agricultural gases is key because it provides accurate data for assessing actual emissions and making informed decisions. This information enables farms to identify problems, adjust practices, and improve efficiency without relying on uncertain estimates.

Measuring these gases also helps ensure environmental compliance and optimise production processes, reducing environmental impact. With proper monitoring, farms can move towards more sustainable and competitive models.

What technology does Kunak offer for the agricultural sector?

Kunak provides modular systems capable of monitoring gases such as CH4, NH3, CO2, H2S, and VOCs, as well as particulate matter (PM), designed to adapt to diverse agricultural and livestock environments. These units deliver precise, continuous measurements even in challenging conditions. An advanced analytics platform processes data in real time, facilitating emission management and decision-making. With these tools, producers can optimise operations and reduce environmental impact efficiently.

Livestock farms that integrate technologies to mitigate their emissions not only minimise their footprint on the atmosphere, but also generate additional income via biogas and ESG certifications.

Towards cleaner livestock farming

Livestock and agriculture are no longer synonymous with uncontrolled emissions — they are becoming living laboratories of atmospheric innovation, where each sensor, additive, and floating cover helps chart the path towards a productive, compliant, and socially valuable sector.

Rural digitalisation, with platforms such as Kunak AIR Cloud that integrate pollutant data (NH3, CH4, PM2.5, and more) from high-resolution measurements (per minute/hour, geolocated) capturing real variations rather than monthly averages, is emerging as a key driver of sustainability. A 20-30% reduction in the carbon footprint of facilities secures CAP bonuses, and positions agricultural operations as ESG leaders recognised for their verified traceability.

Having strategic partners such as Kunak allows farmers and institutions to increase productivity, protect community health, and gain competitive advantages. Continuous monitoring empowers data-driven decision-making. The agriculture that sustains us must feed the world — but it must also breathe with it.

References

- Prajesh, P.J., Ragunath, K., Gordon, M. & Neethirajan, N. (2025). Satellite-Based Seasonal Fingerprinting of Methane Emissions from Canadian Dairy Farms Using Sentinel-5P. ArXiv e-prints. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.00756

- Pardo, G., del Prado, A., Fernández-Álvarez, J., Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R. & Belanche, A. (2022). Influence of precision livestock farming on the environmental performance of intensive dairy goat farms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 351. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652622011386

- Nugrahaeningtyas, E., Lee, J. S., & Park, K. H. (2024). Greenhouse gas emissions from livestock: sources, estimation, and mitigation. Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 66(6), 1083–1098. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2024.e86

- EmiLi24 Symposium (2024). 5th International Symposium on Gas and Dust Emissions from Livestock. https://emiliconference.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Book_of_abstracts_EmiLi24.pdf

- Jaisli, I. & Brunori, G. (2024). Is there a future for livestock in a sustainable food system? Efficiency, sufficiency, and consistency strategies in the food-resource nexus. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2024.101496

- Tai, A.P.K., Luo, L. & Luo, B. (2025). Opinion: Understanding the impacts of agriculture and food systems on atmospheric chemistry is instrumental to achieving multiple Sustainable Development Goals. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 25, 923–941. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-923-2025